The Perks of Writing & Thinking in Two Languages

Why is it easier to write in English rather than my mother tongue?

Croatian and English may both belong to the Indo-European language family, but they’re worlds apart.

Ask a native English speaker to pronounce consonant-heavy words like “Žnjan” or “prst,” and you’ll probably hear them struggle to get their tongue around it.

Also, ask a Croatian speaker to read “thorough” or “choir,” and you’ll likely get sent back to your mother’s reproductive organs!

If only pronunciation were the biggest challenge for bilinguals, trilinguals, or even polyglots.

The bigger question that bugs me the most is: why is it sometimes so much easier to think and write in English?

Sure, part of it is the dominance of English in pop culture and online. Even before the digital age, English had already established itself as a lingua franca—the language of education and status. Also, growing up in the ‘90s, I practically lived on a diet of Cartoon Network and MTV (back when MTV still played music videos).

Another part of it is in, well, the language itself.

Take the sheer number of words in English. The second edition of the Oxford English Dictionary contains about 600,000 words. Out of those, around 170,000 are currently in use, with another 47,000 that have fallen out of fashion.

Croatian, by comparison, has around 400,000 words, though it’s unclear how many of those are actively used today. I suspect it’s fewer, partly because Croatian has absorbed so many English words—especially in business and online communication. Some are adopted directly, like “stage” or “content marketing,” while others adapted to the Croatian alphabet and pronouciation—“menadžer” for manager, or “krindž” for cringe.

This influx of English has edged out certain Croatian words, pushing them into more formal or niche contexts. A good example is the word “elokventan,” (eloquent) which we now use instead of the archaic but beautiful “blagoglagoljiv” (“glagoljati” - an old word for talking; literal meaning is “to verb”).

And among fellow kids, “pliz” and “sori” have replaced “molim te” (please) and “oprosti” (sorry), making these words feel stiff or even awkward.

This is also why it’s hard for me to use Croatian in writing fiction. When I try to express more “contemporary” ideas in Croatian, it often feels like I’m speaking with a broom up my ass (as the Croatian phrase goes).

English, on the other hand, lets me play with language, freely mixing formal and informal registers without sounding outdated.

Another reason I find it harder to write in Croatian is its lack of nuance. This is especially frustrating when I’m writing fiction. I’ll have a fully formed thought, but by the time I try to express it in Croatian, it feels like it loses its color and depth. I either leave a gap or settle for a word that’s close—but not quite right.

For example, I always struggle with the word “ljubazan”, which in English means “polite”, rather than “kind”. And I miss a Croatian version of “kind”! The closest I can get to “kind” in Croatian is “nježan”, but that word actually means “gentle”.

English, on the other hand, feels much more nuanced. Just take simple words like “good,” “bad,” or “run.” These words can have dozens, if not hundreds, of meanings depending on the context. This flexibility makes English more playful and better suited for creating new expressions when necessary.

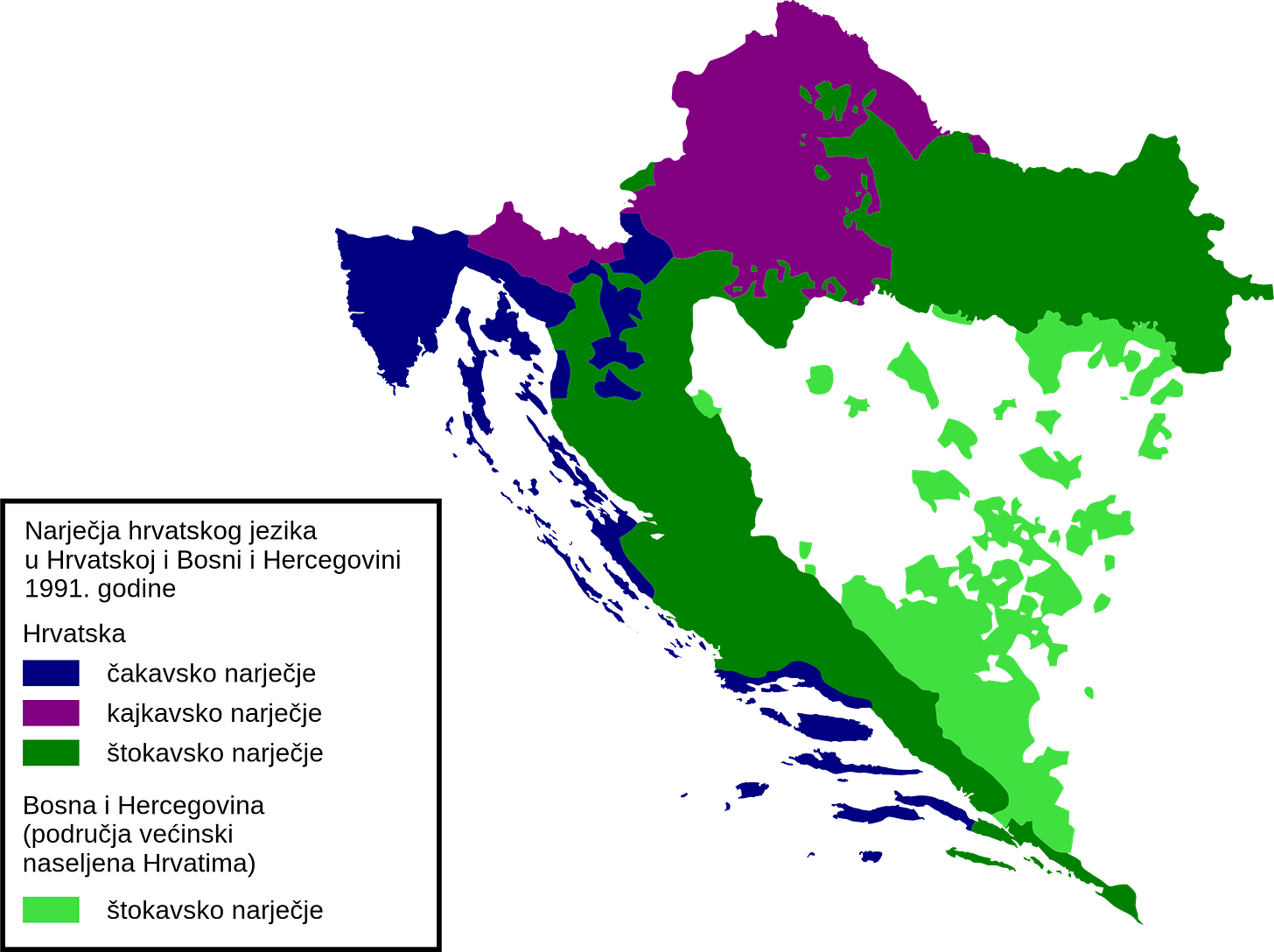

Croatian could have this same richness, but in a different way. Despite being a small country (Romania is five times larger), Croatia is rich in dialects—Štokavian, Kajkavian, and Čakavian. Words and phrases from these dialects could help fill the gaps left by the standard language (which is based on Štokavian).

Unfortunately, Croatian education and language policies discourage the use of dialects and regional expressions. Speaking anything outside of standard Croatian (especially its version used in Zagreb) is often viewed as uneducated or socially inferior.

Take the Dalmatian dialect, for instance. People from Dalmatia are often stereotyped as lazy or rough around the edges, and this stereotype gets reinforced in the media. Characters with these traits tend to speak in a Dalmatian accent, while the “cultured” or educated characters speak in standard Croatian or Zagreb slang. Nowadays, kids rarely hear accents or speech outside of the standard.

Many of these issues are rooted in politics, so it’s too complicated of a matter to fully unpack here.

In a perfect world, I’d love for us to draw from all dialects and regional expressions when the standard language doesn’t quite capture what we want to say. But for now, I’ll work with what I’ve got.

That said, I’m not writing this out of frustration. Actually, as I was writing, I realized that I don’t have to choose between English and Croatian. Some thoughts, feelings, and concepts are simply easier to express in Croatian, while others flow more naturally in English. Both languages are a part of who I am, and they’ve shaped the way I see the world—with all their quirks, limitations, and possibilities.

So, if you’re also juggling two or more languages, the best thing is to accept and embrace it.

If you’re a (fiction) writer, play with syntax and grammar. Invent new words or phrases, borrowing from both English and your native tongue. Also, think of all the puns and innuendos you can come up with!

After all, language thrives when it’s spoken and written freely, not when we’re forced to follow rigid rules imposed by convention and legislation.

The original version of this article was published on the Multilingual Writers Substack.

It's true that it's often easier to write in English than Croatian :( But I guess we need to try to play with words in our own language more - Croatian can also sound pretty nice when written well (as you would know ;))